|

Gedenkgottesdienst zum Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges nach 60 Jahren in Liverpool

Das Gedenken zum Kriegsende in Europa und in Japan legte die englische Regierung auf den 10. Juli fest. Zu den Gottesdiensten anlässlich des 60. Gedenktages luden sich die Kirchen wechselseitig nach Köln und Liverpool ein. Die Kölner, ökumenische Delegation – bestehend aus neun Hauptamtlichen, zwei Ehefrauen und Töchtern sowie fünf jungen Leuten aus der Jugendarbeit – verbrachte ein langes Wochenende in der Partnerstadt.

Gedenkgottesdienst

Das Team der anglikanischen Kathedrale gestaltete mit der British Legion (Veteranenwerk) und der Liverpooler Ausbildungseinheit Cadet Forces den Gottesdienst, der mit dem „Spitefire Prelude“ von William Walton eingeleitet wurde.

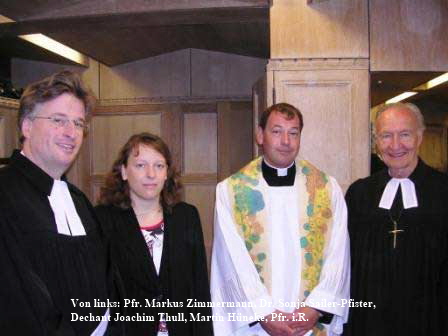

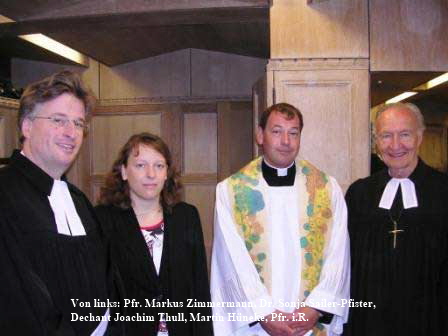

Als offizielle Repräsentanten nahmen die Bürgermeister/-innen aus der Region Merseyside, der Liverpooler Lord Major, in Vertretungen der Königin der Lord-Lieutenant of Merseyside sowie in Vertretung der Ordnungsmacht The Sheriff (zur Zeit ein Frau) teil; zwei von ihnen verlasen Bibeltexte. Gemeinsam mit dem Kathedralen-Team zogen auch die offiziellen Kirchengäste aus Köln und Japan ein. Die Veteranen - angekündigt von einer Orgelfanfare – durchschritten mit 26 Standarten im Slow-March die gesamte Kirchenlänge. Zu einem wichtigen Punkt des Gottesdienstes versammelten sich einige von ihnen um den Altar. Mit gesenkten Fahnen wurde aller gedacht, die in der Armee, Handelsmarine und im Heimatland gedient haben. Daran schloss sich die Kohima Erklärung an: When you go home, tell them of us and say „For your tomorrow we gave our today“. Begleitet von einem Trompetensolo wurden Kränze in der War Memorial Chapel niedergelegt. Beim anschließenden Gebet für die Menschen der Welt sprachen auch Joachim Thull (Dechant in Porz) und Markus Zimmermann (in Vertretung für den Stadtsuperintendenten) einige der Fürbitten; auch Martin Hüneke, Pfr. i. R. und Sonja Sailer-Pfister (in Vertretung für den Stadtdechant) waren mit dem Gottesdienst-Team eingezogen. Die Predigt hielt der katholische Erzbischof Patrick Kelly, der Verbindungslinien zwischen dem Predigttext nach Micha 4, 1-5 zum damaligen und heutigen Familienleben sowie zum Bombenattentat drei Tage zuvor in London zog.

Das Zeichen der Versöhnung und Zukunftshoffnung bildete der „Act of Renewal und Rededication“: Rainer Will überreichte namens der „Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Christlichen Kirchen in Köln“ einen Herrenhuther Stern an Martyn Newman für die „Churches Together in the Merseyside Region“. Junge Leuten aus Liverpool, Köln und Japan drückten abwechselnd ihre Verpflichtung aus, für Frieden, Gerechtigkeit und Wohlstand für alle Menschen in der Welt zu arbeiten.

Schließlich umringten alle Veteranen mit Fahnen den Altar, und die Gemeinde sang die Nationalhymne.

Als Gruß an die Krone marschierten die ehemaligen und aktiven Soldaten – begleitet von einer schottischen Dudelsack-Band – zunächst am Lord-Lieutenant vorbei und gingen dann über die Hope Street zur katholischen Metropolitan Kathedrale; eine britannisches Musik-Chorps der Marine – Bagad De Lann-Bihoué - schloss sich ihnen an.

Celebration of the Sea; Gottesdienst zum Sea Sunday

Am Nachmittag wurde in der katholischen Kathedrale ein Sea-Sunday-Gottesdienst durchgeführt. Liverpool und sein Bewohner lebten früher von der Seefahrt; heute kommen noch immer 94 Prozent der Versorgungsgüter auf dem Seeweg nach England. Lieder rund um die Seefahrt trugen Schulkinder, Shanty-Chor und eine Konzertsängerin vor; zum Gesang wurde auch getanzt. Ehemalige und heutige Pfarrer der Seefahrer-Mission, der Lord Mayor und der Geschäftsführer einer Entwicklungsgesellschaft teilten sich die Texte zur Information, zum Gedenken sowie Gebete und Segen.

Der Sonntag klang mit einem Besuch am Strand und dem Sonnenuntergang bei Temperaturen um die 20°C aus.

Zu Gast in der Deutschen Gemeinde Liverpool

Das Begleitprogramm führte die Kölner Delegation auch in die Deutsche Gemeinde. Hier wurde die 18-köpfige Gästegruppe freitagabends freundlich empfangen und lecker versorgt. Das „Mitbringsel“ war ein Vortrag von Marten Marquardt, früher selbst Pfarrer in dieser Gemeinde, zum Thema „Demokratie und Frieden“. Er ging der Frage nach, warum es so schwer ist, in islamischen Ländern wie Irak, Afghanistan, Palästina das westliche Demokratie-Modell einzuführen. Er betrachtete die deutschen Erfahrungen im Jahr 1945 und damit die Probleme mit der Kommunikation zwischen Kriegsgewinnern und -verlierern und mit ihren unterschiedlichen Wertverständnissen sowie die innere Neu-Orientierung und Vergangenheitsbewältigung in der deutschen Gesellschaft (englischer Text: Anhang)

Christlich-muslimische Begegnung

Samstags waren die Kölner zu einer Diskussion mit muslimischen Leitern eingeladen, die über ihre Alltagserfahrungen als religiöse Minderheit mit britischem Pass in der englischen Gesellschaft berichten. Dorothee Schaper, in Köln zuständig für die Förderung von christlich-islamischer Begegnung, knüpfte insbesondere Kontakte zu muslimischen Frauenorganisationen.

Das gemeinsame Statement muslimischer Organisationen und christlicher Kirchen in Großbritannien mit der Verurteilung des Londoner Attentats als verbrecherischem Akt gab die Richtung vor. Auch die Gedanken des anglikanischen Erzbischofs Rowan Williams zum 8. Juli lagen vor; er ermutigt, nicht in tödlichem Schweigen und in Lähmung zu verharren, sondern das Schweigen für tiefes Durchatmen und Sammlung unter die christlichen Wurzeln zu nutzen (beide Text: s. Anhang)

Projekt „Peace Education Center“ in den Ruinen von St. Luke’s Church

Es folgte der Besuch eines historischen Segelschiffes (zu Gast aus dem norwegischen Marine-Museum in Stavanger) in den modernisierten Albert Docks mit der Einladung zum Lunch.

Dann konnten die Gäste wählen zwischen dem Evensong in der Kathedrale und dem Besuch in der Kirchenruine von St. Luke’s Church. Zu Gast bei Philip & Enid Lodge wurde die Diskussion über ein Friedenserziehungszentrum vertieft. Pläne für den Kubus, der in die alten Kirchenmauern eingesetzt werden soll, sind vorhanden; noch fehlt es an breit getragenem Engagement und der Finanzierung. Im Mai hatte Philip Lodge Kontakte zum NS-Dokumentationszentrum in Köln geknüpft.

Die Kölner Delegation war wiederum privat untergebracht; zum Abschied hatte sie reichlich Grund, sich bei den privaten Gastgebern und Martyn Newman als Programm-Verantwortlichem zu bedanken.

Hannelore Morgenstern-Przygoda, 15.07.05

Kölner Delegation:

Martin Hüneke/Bad Iburg, Marten & Reinhild Marquardt, Hannelore Morgenstern-Przygoda/Sozialwerk, Sonja Sailer-Pfister, Referentin des Stadtdechanten; Dorothee Schaper, christlich-muslimische Begegnung; Dechant Joachim Thull Köln-Porz, Markus Zimmermann (i.V. Stadtsuperintendent Fey) und Ehefrau Susanne, Rainer und Eva-Maria Will mit den Töchtern Caroline und Cornelia sowie 5 Jugendliche: Robert Förderer, Frank Obermüller, Sebastian Witte, Martin Cornet, Bernadette Cremer

|

Western societies under US leadership are at present fascinated by the idea that we ought to bless all sorts of countries around the world with our European achievements of peace and democracy, or rather shorter: a peace loving democracy. Honourable as this intention may be, I am afraid the instruments that are being implemented to bring about a democratic turn of the tide are ill designed. I cannot help but introduce a little irony into the tale.

Western societies under US leadership are at present fascinated by the idea that we ought to bless all sorts of countries around the world with our European achievements of peace and democracy, or rather shorter: a peace loving democracy. Honourable as this intention may be, I am afraid the instruments that are being implemented to bring about a democratic turn of the tide are ill designed. I cannot help but introduce a little irony into the tale. I shall give you three examples of extremely well intended but at the same time extremely ill accepted offers made by allied officers to different addresses in Germany in the year 1945. And let me stress this right in the beginning: I admire the British for their patience and their humane endeavour to bring peace and democracy into our totally corrupted country in 1945. We cannot and indeed must not forget, what the British and their allies have done for us and for the liberation of Europe from Nazi terror.

I shall give you three examples of extremely well intended but at the same time extremely ill accepted offers made by allied officers to different addresses in Germany in the year 1945. And let me stress this right in the beginning: I admire the British for their patience and their humane endeavour to bring peace and democracy into our totally corrupted country in 1945. We cannot and indeed must not forget, what the British and their allies have done for us and for the liberation of Europe from Nazi terror. These three rather random examples of best intentions on the one hand and simple but seemingly inevitable misunderstandings on the other may suffice to say: peace, democracy and Christianity are not at all a self explaining set of values for a future world. There can be so much tension between those three ideals, that they cannot be taken as an automatic road towards a better future.

These three rather random examples of best intentions on the one hand and simple but seemingly inevitable misunderstandings on the other may suffice to say: peace, democracy and Christianity are not at all a self explaining set of values for a future world. There can be so much tension between those three ideals, that they cannot be taken as an automatic road towards a better future. But eventually they all were pressed so hard that the protestant Church in Germany formulated the so called “Stuttgarter Schuldbekenntnis” (Stuttgart confession of guilt) in August 1945. The result is a rather ambiguous paper, rather half hearted as far as radical penance is concerned, but it was a first step onto the road of conversion. In Germany this road was later ambiguously labelled “Vergangenheitsbewältigung” (the management of the past; to master the past; the struggle to come to terms with our own past). Many Germans avoid this expression, because it is so ambiguous. On the one hand it stresses the need to really look back and judge our own past; but on the other hand and at the same time it opens the path towards an end of discussion, full stop. We have looked back, and now we have done our duty; and therefore we need no longer be reminded of the past by any one from outside or inside Germany. The road now is open into the future. – Although I am well aware of the most problematic connotations of this expression “Vergangenheitsbewältigung”, I have recently come to use it in quotation marks: there is a certain historic post war lesson woven into this ambivalent expression, and this lesson I don’t want to forget.

But eventually they all were pressed so hard that the protestant Church in Germany formulated the so called “Stuttgarter Schuldbekenntnis” (Stuttgart confession of guilt) in August 1945. The result is a rather ambiguous paper, rather half hearted as far as radical penance is concerned, but it was a first step onto the road of conversion. In Germany this road was later ambiguously labelled “Vergangenheitsbewältigung” (the management of the past; to master the past; the struggle to come to terms with our own past). Many Germans avoid this expression, because it is so ambiguous. On the one hand it stresses the need to really look back and judge our own past; but on the other hand and at the same time it opens the path towards an end of discussion, full stop. We have looked back, and now we have done our duty; and therefore we need no longer be reminded of the past by any one from outside or inside Germany. The road now is open into the future. – Although I am well aware of the most problematic connotations of this expression “Vergangenheitsbewältigung”, I have recently come to use it in quotation marks: there is a certain historic post war lesson woven into this ambivalent expression, and this lesson I don’t want to forget. particularly in the Rhineland area, for the way you have helped us go forward by looking back and facing realities. And I would like to mention one British bishop in particular, who with his very special mixture of love and demand supported Dietrich Bonhoeffer during the years of terror and who also after the war did all he could to help us look back and thereby look forward at the same time.

particularly in the Rhineland area, for the way you have helped us go forward by looking back and facing realities. And I would like to mention one British bishop in particular, who with his very special mixture of love and demand supported Dietrich Bonhoeffer during the years of terror and who also after the war did all he could to help us look back and thereby look forward at the same time.